Pope Invites Waibel to Vatican To Advise on AI

SCS Professor Joined Esteemed Thinkers for AI Working Group

By Bryan Burtner

Media Inquiries- Language Technologies Institute

The rapid rise of artificial intelligence technologies brings with it questions technological and practical, but also philosophical.

Earlier this fall, Pope Leo XIV invited Alex Waibel, a professor in Carnegie Mellon University’s Language Technologies Institute (LTI), and other world-renowned thought leaders in AI to the Vatican to work through the thorny questions surrounding AI.

The AI and Human Fraternity Working Group, part of the Vatican's third edition of the World Meeting on Human Fraternity, met Sept. 12 and 13 in Rome. Waibel was one of 12 invitees, whose backgrounds spanned science, entertainment, culture and religion.

“I went into this with a bit of trepidation,” Waibel said, explaining that he feared participants might censor themselves somewhat in hopes of avoiding conflict. “But it was quickly clear that we all really had the same concerns.”

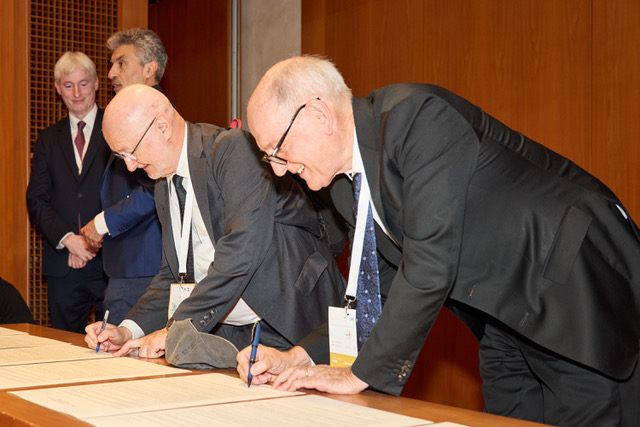

The product of the Working Group is a jointly drafted open letter, “Fraternity in the Age of AI: Our Global Appeal for Peaceful Coexistence and Shared Responsibility.” Addressed to Pope Leo, global leaders and “all people of good will,” the letter acknowledges the crucial inflection point that humanity is at with regard to responsible AI development. It also lays out 11 guiding principles upon which safe and ethical AI research and policy should be based. Chief among them is that “AI must never be developed or used in ways that threaten, diminish or disqualify human life, dignity or fundamental rights.”

Waibel, who also holds a faculty appointment at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and whose work focuses on speech recognition, machine translation and human-computer interaction, said working group members came from “all over the board” in terms of both their backgrounds and areas of expertise, as well as their perspectives on the future of AI. They included Nobel Prize winner Geoffrey Hinton, Turing Award winner Yoshua Bengio, Grammy-winning recording artist will.i.am and others from the worlds of computer science, business and human development.

Waibel considered the juxtaposition of computer scientists and AI pioneers with social scientists, activists and theologians to be a surprisingly natural one.

“AI is an interesting thing in that it doesn't take very long before you start talking about things that border on philosophy or religion,” he said. “People say, ‘Well, if AI takes over what will become of humans? What makes us special as humans?’ And so all of this really touches on sensitive issues that most people have some opinion on.”

In addition to advising policymakers and industry leaders around the world, the working group’s letter may inform the writing of papal encyclicals — pastoral letters that establish church doctrine and provide guidance on matters of great significance — and other texts distributed by the pope and senior Vatican officials. On Nov. 7, Pope Leo called on AI builders to “cultivate moral discernment as a fundamental part of their work” in a post from his X account.

Specific guidelines suggested in the letter include pronouncements that only humans should have legal agency or personhood, that AI systems must never make life-and-death decisions, that the benefits of AI should not be monopolized, and that the use of AI must be ecologically responsible, among others.

Waibel said each participant brought their own subjects of primary concern to the group. For him, a major point of emphasis was the danger of AI systems that are actually less intelligent and trustworthy than users expect them to be — as opposed to the common concern that AI is so intelligent that it could make humans obsolete.

"People sometimes project too much into AI,” he said. “They assign religious or psychiatric or philosophical or even romantic feelings and attachments to a tool, which in principle I think is wonderful. But it is, and should remain, nonetheless only a tool.”

This thinking influenced one of the first directives listed in the letter, that “AI must be used as a tool, not an authority,” and must always remain under human control.

Waibel said sycophancy (the tendency to produce overly agreeable or flattering responses) in some large language model-based (LLM) systems is one of the more worrisome types of what he calls “illusions and delusions,” that can make AI agents fallible and “dangerously persuasive.”

These illusions and delusions, Waibel explained, can pose risks both unintended — such as when an AI tool inadvertently provides responses that are untruthful or potentially harmful because it predicts they will please the user — and nefarious. Social media companies and content platforms could tune their own AI agents and algorithms to subtly influence the thoughts and behaviors of users, driving engagement while also shifting public opinion and fomenting public discord.

Ultimately, Waibel said, long-term success in ensuring responsible and ethical development of AI will likely require both technical and political efforts. Initiatives on the technical side could include research into effective safeguards that can be built into AI systems and buy-in within AI companies to implement those techniques. Political efforts may feature legislation to impose rules like the ones proposed in the working group’s letter.

“I think it’s a bit naïve to think that widespread prohibitions on AI research will be effective, because it’s a race and nobody wants to be behind in that race,” Waibel said. “But I think we as scientists are called on to understand the dangerous implications and to develop training methods that mitigate those implications. Let’s come up with objective functions and technical mechanisms to make sure that the development of these machines happens in a way that we think is good for society, and then go to companies and say ‘Look, we have a better alternative.’”

Waibel noted that CMU is well-positioned to be a driving force in this project.

“That’s our opportunity. We have some of the most talented AI researchers in the world, and I think if we all put our heads together, we could develop these tools and at the same time be active on the policy side,” he said, adding that effective communication between scientists, the public and government officials is crucial to their success.

“In that sense, I think having public declarations like the one that came out of the working group is important,” he said. “But it can’t stop there. It needs to be supported technically and not just be a vague prohibition.”

For his part, Waibel feels that his experience at the Vatican made him even more invested in ensuring that AI progresses in a way that’s consistent with the needs, and the safety, of society.

“I think it’s sensitized me more than I was before,” he said. “I wouldn’t say it fundamentally changed my views, but it certainly deepened the concern. And in my view it doesn’t have to be pessimistic.

“I have to believe in humans still wanting to be humans,” he said, “And not wanting to be overtaken by machines, and that we can figure out a way to make sure that that happens.”